[KWE Note: James Vittitoe died July 25, 1994. This memoir was submitted to the Korean War

Educator in his memory by his brother, C. Hagan Vittitoe, and with permission of James' widow, Janet Vittitoe.]

Passing Thru...

Introduction

Without elaborating too much on details, "Passing Thru" gives you the story of my life: my childhood during the

Depression years of the 1920s and 1930s, followed by the war years of the 1940s and 1950s, and then the post-war

years of unparalleled economic and technical growth.

Aviation has been my life’s work for more than 50 years. As a pilot, I have flown more than 20,000 flight hours

in some 50-60 different types of aircraft and helicopters. I must say there have been a few moments of panic;

however, I wouldn’t change anything. I have known people who worked in jobs they hated and could hardly wait to

retire. So my suggestion to you is this: Whatever you do in life, do it because you enjoy it, not just because

it’s a meal ticket.

– Jim Vittitoe

My Childhood

My early childhood memories are of a small central Kentucky railroad town, Cecilia, where the townsfolk would

meet the trains just to see who was arriving and departing this metropolis of about 100 souls—including me.

Saturday was the big day of the week when most of the local farmers would come to town to sell their produce, buy

dry goods from Mr. J.C. Harrold’s general store, and sit around on his front porch telling stories of bygone

times. My grandfather, Thomas Hagan (1855-1943), who most people called Uncle Tom (I called him Pap Paw), had

traveled more than the others and was regarded as worldly. Most had been no farther than the county seat, six

miles away.

Pap Paw came from a large Catholic family. They were determined that one son would be a priest, and guess what:

Pap Paw was elected. However, just prior to being ordained, he left the monastery, joined the Masonic Lodge, and

was forever an outcast from the family. No one ever knew what experience or disillusionment perpetuated this

drastic change in his religious view.

It was during his travels as a lumber buyer that he met my grandmother, Mollie Harding (1863-1934), a school

teacher from Campbellsville, Kentucky. Everybody called her Aunt Mollie. (I called her Mam Maw.) They were married

April 3, 1893 in Campbellsville, Kentucky. Pap Paw’s father and mother owned several thousand acres of land and a

number of slaves. But with the Northern and Southern armies going back and forth through that area taking what

they needed, there wasn’t much left except the land by the time the Civil War ended.

Although Pap Paw had 11 brothers and sisters, without the slaves there was no way to work the farm. They had to

start selling off the land to pay taxes. Pap Paw bought 100 acres, and he and Mam Maw set up housekeeping in an

old log house that had been slave quarters. Uncle Albert and my mother, Esther Hagan Vittitoe (1895-1988), were

born in this log cabin.

By the time my mother was in her teens, Pap Paw and Mam Maw had built a large two-story home just off old

Litchfield Pike Road. My dad, James Lafe Vittitoe (1889-1953), grew up on a neighboring farm. His dad, Raleigh

(1853-1895), was a deputy sheriff in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, a position of prestige. Raleigh was killed on his

way to stop a disturbance in a local saloon – shot dead before he got through the door by a gunshot from inside.

The story was told that a Negro handyman who had never owned a gun in his life was hanged for the murder. No crime

could go unpunished in those days, and a poor illiterate black man was an easy scapegoat. To the townsfolk,

justice was served. Dad’s mother, Susan Patterson Vittitoe (1856-1896), died shortly thereafter. Dad had two

brothers and one sister, and the four young orphans were then raised by relatives. Dad was raised by an uncle and

aunt named Criger on a farm not far from Pap Paw’s place. Two children were killed very young when they were

caught on a railroad bridge and hit by a train.

Mother and Dad were married on May 22, 1919. No one ever told me whether they had any medical training, but

they both worked in a hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio. When World War I was over, they returned to Cecilia and Dad

started working on the Illinois Central Railroad southwest of town near Princeton and Paducah, about 100 miles

away.

In those days of limited careers, if a person didn’t farm, he worked for the Illinois Central Railroad. Dad got

home most Friday nights and returned on Sunday. Mother coped with whatever Dad earned, which wasn’t much at that

time. I remember eating a lot of salmon fish patties, except on Sundays after church when we would go to Pap Paw

and Mam Maw’s for Sunday dinner. Mam Maw always set a fancy table with fried chicken, biscuits and gravy.

Mother was afraid of her shadow in those days as there were always tales of hobos traveling through town on

freight trains, robbing and killing people … more tall tales than fact. I was born March 15, 1920. My brother

Lloyd was born August 25, 1923. Hagan was born September 6, 1925. We lived in a two-bedroom home, but when Dad was

away, we all slept in one bed: Mother on one side, Lloyd and Hagan in the middle, and me on the other side. Mother

always put Dad’s pistol under her pillow. I was never sure whether it was loaded, and by morning the pistol could

be any place in the bed. We three kids were probably in more danger nightly from the pistol than we were from

interlopers. One night our 90-year-old neighbor scratched on the window screen, and Mother had the pistol pointed

at her and was ready to fire before she realized who it was. I’m not sure she could have even hit the window, but

it scared us all nonetheless.

Life remained on an even keel until I was around six and Hagan was a year-old baby and Dad was hurt on the

railroad. He was on a motor car that derailed, and he was hit on the head by a railroad jack handle, an accident

that put him in the railroad hospital in Chicago. Shortly after he returned to work, he started having epileptic

seizures—not the convulsion type, but the kind that would cause him to stop whatever he was doing or talking about

and pull on a chair, table, or anything near. After a couple of minutes he would recover, but would not remember

what he was doing or saying. The railroad company laid him off. In today’s world, he would have been medically

retired, but not in those days. Workers’ compensation, disability, and welfare were unheard of protection in a

laborer’s contract in the 1920s. The country was about to sink into a deep depression.

With Dad out of work and bills piling up, something had to be done. Mother wrote to various hospitals in

Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio. By a lucky coincidence, one of the doctors Mother and Dad worked with in Cincinnati

was now head of the Indiana State Mental Institution in Richmond, Indiana, and the hospital needed a husband and

wife to be in charge of a ward of about 40 patients. He offered Mother and Dad $30 a month to take the jobs, which

was a godsend. The hospital was unaware of Dad’s condition, so in a sense, Mother had an extra patient to worry

about. Employment qualifications were less comprehensive than they are today.

The next hurdle was what to do with three boys. They decided that Lloyd and I would stay with Mam Maw and Pap

Paw, and Hagan would be boarded out near the hospital in Richmond. They owed Mr. Harrold about $300 for rent and

groceries that had been charged at his store, and after a lengthy discussion, agreed to pay him on a monthly

basis, depending on what they could afford.

Lloyd and I moved in with Pap Paw and Mam Maw on their farm, a mile from town. At that time, Pap Paw was nearly

70 years old and Mam Maw was around 65. Both were avid readers. Pap Paw studied various religions, but I guess he

never settled on one; I never saw him in church. Mam Maw was a strict Baptist, and she had Lloyd and me in church

every Sunday, rain or shine.

Pap Paw’s farm included about 30 acres of wooded forest, which became my hunting ground. Uncle Albert bought an

acre from Pap Paw and put up a service station, though I heard later that he sold more "white lightning" than

gasoline. Uncle Albert was a great hunter. He gave me a .22-caliber rifle and taught me to shoot. The most

pleasure I had during those years was hunting in the woods with Uncle Albert or hunting by myself. I was seven or

eight years old – practically a young man.

Pap Paw was one of those people who would get up before the chickens at 4 a.m. each morning. He’d feed his two

mules, the cow and the chickens and return to the house about 5:30 a.m. for a breakfast Mam Maw would have ready

after building a fire in the old wood-burning stove. They would work all day, Pap Paw on the farm and Mam Maw in

her garden. Food was no longer a problem; Mam Maw canned food for our needs. Other necessities such as clothing

were a little harder to come by, but fortunately bib overalls were the uniform of those years and we commonly

needed only shoes and long-handle underwear (also known as long johns) in the winter.

I went to a one-room school in Cecilia, which was like most country schools those days – one teacher for eight

grades. It was only a mile each way from Pap Paw’s place to the school, but it seemed like 10 miles in good

weather or bad.

On a beautiful fall afternoon in 1929, just shortly after school started, a dramatic even occurred that

probably had a profound and lasting effect on my young life. I saw my first airplane, a little red biplane that

circled the schoolhouse and landed in a nearby field. The teacher dismissed us from our studies so that we could

all go outside to see this wonderful flying machine. The pilot stepped out, a young fellow in his early twenties,

dressed in riding boots, britches, leather jacket, helmet and goggles. He had flown down from Louisville to see

his girlfriend, a nearby farmer’s daughter. It was something out of this world to us kids. He told us about flying

and said it was dangerous, that the life expectancy of a pilot was only five years. Oh, but what a way to go even

if it did last for only five years! That started my dream of flying, although I didn’t think it would ever happen.

In the spring of 1930, Pap Paw and Mam Maw told mother that they could no longer take care of Lloyd and me.

They were getting up in years and could hardly take care of themselves. That spring Mother and Dad came home and

brought Hagan with them. They located a cousin, Ina Yates Wallace, whose husband Lou had lost his garage business

in Louisville in the depression. Lou was a great mechanic, made the first automobile wheel wagon I’d ever seen.

Ina and Lou agreed to board the three of us.

We moved three or four times before Lou found an old farm that he liked. No one had lived there for years and

it was run down and in need of considerable work, but it had a big log house that was comfortable, so we settled

in. Lou got two mules, one that would get through any fence Lou put up. One day he loaded his shotgun with rock

salt and when that old mule started through another fence, he shot that mule in the rear end and damned near

killed it. He spent the next two weeks trying to save its life. I put in a lot of time behind those mules, plowing

and working the farm. I’m not sure what happened to school those two and a half years. Our education was suspended

by necessity, and no one seemed to mind.

In 1932, Dad started having 10-12 seizures a day. The doctors where he worked became aware of this and

recommended that he be put in the Indiana State epileptic hospital, which was a large farm where patients worked

and took care of each other. The farm was located in New Castle, Indiana, not far from Richmond. With only half

the income, things got bad for Mother and she could no longer board us with the Wallaces, pay her debts at Mr.

Harrold’s and take care of herself. With the help of the Baptist Church at Cecelia, we were put into the Kentucky

Baptist Children’s Home at Glendale, Kentucky. It was only about 20 miles from Pap Paw and Mam Maw’s place, but it

might as well have been 200. I saw Mam Maw only one time after that and she was very sick. She and Pap Paw had

agreed that when the first one died, the remaining spouse would sell the farm and use the money to board and

lodge. The farm sold at an auction for $3,000, and I guess it lasted until Pap Paw died in 1943 at 85 years old. I

saw him only a couple times after 1932, the year we arrived at the Kentucky Baptist Children’s Home.

About 200 boys and girls ranging from babies to teens lived in the children’s home, situated on 700 acres of

farmland. The boys worked the farm and dairy (one of the most modern dairy barns of its time), and the girls did

the laundry, cooking, canning and sewing. We were cared for, but we certainly paid our own way with the work

schedules. The girls’ and boys’ dormitories were separated by the administration offices, dining room and nursery,

so it was a strictly segregated situation except for school and church.

The Nolin River ran through the farm, and there was never a boy raised in the home who could not swim. During

the summer months there were always 10-50 boys swimming in the river. When the river was high and out of its

banks, boys would jump off the old railroad bridge and swim 10 miles downstream around trees, logs, and anything

else in the way. It was a miracle no one drowned. During those four years I was in the home, only one kid died,

from polio. Three others had the disease, but recovered.

I had been there only three months when the girls had a chance to go swimming. It was made clear that the boys

would stay away from the river when the girls went for their dip, but the boys had other ideas. When the girls

arrived, three or four boys were perched in every nearby tree. The girls’ matron soon realized what was going on

and called the superintendent, Reverend Hagland, who arrived in his ole 1930 Model A. Using his car to chase the

kids across the farm, he ended up driving through a wheat field where about 30 kids were sprawled on the ground.

It was amazing he didn’t run over a dozen. How we all survived, I’ll never know.

As sophisticated 10 or 11 year olds, we had to identify a girl as our own. I had been there about two weeks

when I was told that my "girlfriend" was Virginia Wolf. It was another two weeks before I even saw Virginia. I

started picking my own girlfriends, like Geneva Young and Mary Francis Womack. We were all in the same class from

fifth grade on. The one I was a little more serious about was Golda Slusher, one class behind us, to whom I gave

my class ring.

A boy had to be inventive to improve his lot in a place that housed 200 competitors. One of my jobs during this

period was to build a fire in the old wood-burning kitchen cook stove. I would get up about 4 a.m. and have the

stove hot for the matron and girls to cook breakfast. Albert Hicks was my helper. There was never any food in the

kitchen, but behind the locked pantry door there was plenty. I soon learned that, with a pen knife, I could easily

open the pantry door. So any time Albert and I were hungry in the evening or early in the morning, we would help

ourselves and clean up the dishes in the morning while building the stove fire.

One Sunday night when everyone was off to Gilard Baptist Church for evening services, Albert and I were hungry.

We made the pantry run, figuring we would catch up with the other kids returning from church and clean up our mess

the next morning while building the fire. On our way to catch up with the kids returning from church, we noticed a

car turning into the grounds—Reverend and Mrs. Hagland were coming back from a fund-raising trip in Kentucky. Our

worst fear was about to come true; we knew they’d see the two dirty cereal bowls we’d left on the counter. The

Reverend and Mrs. Hagland headed for the kitchen. Those Jack Armstrong cornflakes were like lead in our stomachs.

The next morning, every boy was lined up like a row of corn, and the guilty person or persons was told to step

forward. Albert and I were not about to admit our deed. It was two weeks before the furor settled down and we

found new locks on the pantry door. A good thing was lost forever.

During the next four years, I worked as a farmer, shoe cobbler, bus driver, barber and general handyman. In the

fall of 1932, I resumed school in Glendale, three miles from the home. Except for the small children, we all

walked the three miles to and from school. At 12 years old, I was put in the fifth grade.

In 1936, I turned 16 and after school was out, I had to leave the home. John Gardner, the basketball coach,

wanted me to stay with his folks in Glendale and play ball the next year. However, I went to Richmond, Indiana,

and Mother found a place for me to board near the sanitarium. Mother and I visited Dad a couple times that summer,

but otherwise it was a very dull summer. In the fall I went back to Glendale and stayed with Mr. and Mrs. Gardner,

John’s dad and mother. They owned a general store in town, and I worked in the store to help pay for room and

board. I broke no scholastic records that year, but did have a good basketball season.

In the spring of 1937, Mother moved from Richmond to work in the Cincinnati sanitarium, located in the College

Hill section of town. When school was out, I hitchhiked to Cincinnati. Mother found a place for me to room and

board for $5 a week. Mom and Pop Lawson’s had never taken boarders before. I got a job in Wayley’s Drugstore for

$11 a week, 8 a.m. to 11 p.m., six days a week. Wayley’s was the local hangout for the kids in College Hill. We

had the best ice cream in town.

In the fall of 1937, I hitchhiked to Glendale for school and basketball. The summer of 1938, I was back at

Wayley’s Drug Store and Mom and Pop Lawson’s. Each spring when school was out, I told everyone at Glendale that I

would not be back the next school year. John Gardner, the math teacher and basketball coach, Miss Stella Elkins,

history and geography teacher, and Mr. J.M.F. Hays, the principal, always lectured me to return and finish my

studies. Mr. Hays is now 93 years old, and Mr. Gardner and Miss Elkins not far behind. I’m still good friends with

each of them, and we exchange notes at Christmas to this day. The school did not have psychologists and

counselors, but their dedication and encouragement gave me the education I may have missed.

The 1938-39 basketball season was a good one. We won the regional tournament, and I made the second all-state

team. The summer of 1939, Bill Pierce and I hitchhiked to Charleston, South Carolina, to visit my aunt and uncle,

Dad’s brother Raleigh and his sister, Elizabeth Cronin. Sis had no children but Raleigh had four girls and one

boy. For about two weeks, we all had a ball swimming and relaxing at Folly Beach and the Isle of Palms beaches.

Too soon it was time to head back to Cincinnati and on to school. I was ready to leave when Charlie Turkleson,

Herb Dash and Bob Keifel decided to borrow Charlie’s dad’s car and take me to Glendale just to see what that town

was all about. It was a 150-mile drive. We arrived about sunrise. Mrs. Gardner fixed breakfast for all, and then

the others headed back to Cincinnati and I went off to school. Classes had already started.

During Christmas of 1939, I hitchhiked to Cincinnati for the holidays. It was on the trip back to Glendale that

I ran into the first gay I’d ever met. It was just south of Louisville and only 50 miles from home. The car had a

California license and I thought, "Good, he’ll go all the way to Glendale." I had just gotten into the car when he

said he would have to take a detour because the road was closed a little farther down. I thought that was odd; I

had just gone north on the same road a week before. He turned off the main road and it wasn’t long before he put

his hand on my knee. I brushed it off and back came his hand. After he tried a couple more times, I reached into

my overcoat pocket and placed a little .32-cal pistol I had in plain sight of this fellow and told him to get me

back to the main highway – pronto! He didn’t waste time in doing just that. He didn’t know that the gun wasn’t

loaded and I didn’t have a shell for it with me. When I got out of the car, he turned back toward Louisville, and

I thought he was going back to report me to the police. It was five minutes until a bus came by. I flagged the bus

and spent what little change I had left for a bus ride to Glendale. It was nice to get back.

I was never much of a student, but did get an offer for a basketball scholarship from Western Kentucky.

However, by May 1940 when I graduated from high school, I’d had all the school I could handle. (And the other

schools in the district had probably had enough of me. When I graduated from high school, I had just turned 20 and

had played varsity basketball for five years.) Everyone there was aware that I was leaving for Cincinnati the day

after school was out. Mary Francis Womack, my girlfriend at the time, said she wished she were going with me. This

scared the hell out of me. I wasn’t sure how I’d be able to take care of myself, much less a girlfriend. So back I

went to Wayley’s Drugstore in Cincinnati.

The summer of 1940 was a little wild. I was back working at Wayley’s and boarding with Mom and Pop Lawson.

There was more talk of war, but this didn’t affect our summer. I bought an old 1926 Chevrolet for $20, put a $13

clutch in it, and maintained tires from Pearce’s service station. Bill, the younger of the three Pearce boys, was

in our group. Sam Taylor, Charles Turkelson, and I all worked at the drugstore that summer. Herb Dash worked at

his father’s dry cleaning establishment. Bob Keifel worked with his dad as a builder. Bob Webb and Harold Grabo

didn’t work, just played. It was our last carefree summer. Not one of us knew that war would change our lives

forever.

We made the rounds of every bar in Cincinnati that summer. Coke was five cents. Ten High bourbon was ten cents

and beer was about fifteen cents. We also hit Echo and Mount Airy, the parks where the big bands played. No one

had a steady girlfriend except Bob Keifel. That fall Bob married Hassie and bought a house in North College Hill

for $5,000. We told him he was crazy on both counts. How would he ever pay off $5,000? But he and Hassie were

obviously on the right track. They still live in that home 50 years later.

Joining Up

We all went into the military except Grabo. I’ve been told that he got mixed up with the mob and was found shot

to death in downtown Cincinnati. Bob Webb was killed in a B-17 over Germany. Keifel and Dash went in the Navy.

Bill Pierce went into the Navy as a pilot about three classes ahead of me.

It was January or February of 1941 that Turkelson and I were putting new magazines in the rack, including a

LIFE magazine with a cover photo of a Marine in dress blues. I told Turk that was the outfit for me. Mr. Wayley

was nearby and heard the remark. He said we couldn’t make it in that outfit, but Turk and I talked it over and

decided to go to the recruiting office. The sergeant wanted to put us on the next train to Parris Island. We told

him we would think it over and be back to see him. We both quit Wayley’s and took a two-week trip to Charleston,

South Carolina. I sold the old Chevy when we got back and went down and signed up on March 24, 1941. Turk backed

out.

The sergeant gave four of us our orders as he put us on the train to Parris Island. The three with me were

strangers. When we were settled on the train, we opened the orders. There were two $1 bills attached. However, the

orders stated that $3 was for food for the trip. I was told later that the sergeant was reported and court

marshaled for taking $1 from each recruit he sent out.

When we arrived at Port Royal, South Carolina, we were met by a staff sergeant. I have never seen a man’s

uniform started and pressed so well. This sergeant turned out to be our drill instructor. It didn’t take long to

realize that we were in a new ball game. Before the day was out, we all had haircuts and a new issue of clothing.

Despite our changed appearances, I did recognize the three guys I had traveled with on the train.

Well, boot camp is boot camp – all hell. However, the last week was rifle range. By this time the drill

instructor had softened a little. I asked if I could have sea duty after boot camp. He said if I shot expert on

the range, I could have what I requested. Two of us out of 60 made expert rifleman. (My hunting days at Pap Paw’s

undoubtedly helped.) The following week when our orders came in and I got guard company NAS Jacksonville, Florida,

I asked the DI about my request for sea duty. He said I wouldn’t like it, and to take my orders and get the next

bus to Jacksonville. We had learned in boot camp NEVER to argue with the DI. I arrived at NAS Jacksonville around

May 1, 1941. My first assignment was to guard the water tank – four hours on, eight hours off, and four on in a

24-hour period. Then I had two days off. That was a lot of time off with only $21 a month to spend. However, I was

making an extra $5 a month for firing expert on the rifle range. Food and clothing were free and all the laundry

you could send out was $3 a month, so with $23 a month to spend I was in good shape for liberty. Only the last

week of the month was a little tight.

Guard Duty

We had a very sharp young second lieutenant by the name of Wayne Cargill. The lieutenant would make his rounds

day and night and try to catch us off guard. I knew my general and special orders, so I guess this impressed him

and he put me on the main gate after about two months. It was on this duty that I was almost killed. It was policy

that the midnight-to-four watch cleaned the pistols. I had been there about two months when Tom McCarthy and I

were cleaning several .45-caliber pistols. We were straddling a bench facing each other, with the .45s and clips

between us. Sometime during this cleaning process, Tom picked up a .45, pulled the slide and pointed it at my

stomach. I asked Tom who he was trying to kid. He turned his hand slightly and pulled the trigger. The thing went

off and blew a hole in the wall. Needless to say, it scared the hell out of both of us. Lieutenant Cargill never

knew how close it was to hitting me. He put Tom on two weeks’ restriction. When Tom’s folks arrived two days later

for a visit, he had to talk to them through the fence.

With a lot of time off and not much money, I started spending time at one of the hangars where the cadets were

flying. I asked an old chief about going up with one of the student pilots. The chief said if I cleaned the drip

pans he would see that I got my ride. So I cleaned and cleaned and cleaned – and went flying.

Lieutenant Cargill made me a private first class in September 1941. That was very fast as there were Marines

around who had been in the Corps three or four years and hadn’t made PFC yet. I was proud of those stripes.

However, a couple of weeks later there was trouble. When Cargill got to me during the weekly Friday inspection, he

checked my rifle (it was spotless), checked my haircut, and said, "Vittitoe, I went to a hell of a lot of trouble

to make you a PFC and you fall out for inspection needing a haircut." He reached up and ripped my new PFC stripes

off my shirt. I had a haircut on Monday, but he didn’t do any paperwork, so my "demotion" was only intimidation

for the inspection.

Charlie Turkelson came down to visit for a week. We made the town and beaches and had a grand time. Charlie

returned to Cincinnati and joined the Marines. After boot camp, they made him a drill instructor. He hated the

job. He was later made a DI for women Marines, which was worse. Later he got sea duty, but the war was almost

over and he saw little action.

Pearl Harbor is Attacked

In October, Cargill put in for flight school and got his orders, but before he left, I asked him if I could get

aviation duty. He put in the request before he departed for Pensacola, Florida. To make sure I got the orders, I

requested a furlough transfer. That means one pays his own way to the next duty station. Well, my orders arrived

and approved a transfer to Quantico, Virginia, effective Dec. 8, 1941. On Saturday, Dec. 7, I was packed and ready

to leave the next day. When the news of Pearl Harbor was announced, all I could think about was that someone would

cancel my orders. So at midnight, I went out the gate with my sea bag and rifle and hitchhiked to Cincinnati. (I

can’t imagine anyone hitchhiking with a rifle today, even in uniform.) When I arrived, everyone who hadn’t already

joined the service was going into one branch or another. The old town just wasn’t what it used to be.

I heard that my old girlfriend, Goldie Slusher, was in town going to school. I located her, but she was going

with some fellow who asked her not to go out with me. She returned my class ring, and married this fellow. I heard

later that he was killed during the war. Meantime, Charlie’s younger sister Verna had grown up. I had been home

three days, and she and I had one date before I got a telegram from the Commandant of the Marine Corps to report

immediately to Quantico. With sea bag and rifle in hand, I hitchhiked there.

I arrived on December 13 to find that all aircraft that could fly were gone. The squadrons and personnel had

left for the west coast. The two airfields at Quantico were Brown Field and Turner Field. Brown Field was soon

closed; the runways were too short for the newer aircraft. Being a PFC, I was put in charge of overseeing the

barracks clean-up while awaiting an aircraft service school. I had been there about two weeks when the officer of

the day read the orders of the day before lunch, as was customary in those days. This day he started that anyone

interested in volunteering for one of three reserve bases – Gross Ile, Michigan; Minneapolis, Minnesota; or

Anacosta, Maryland – should see the sergeant major after lunch. I told him I would like one of those positions.

I was tired of chasing "boots" around to clean up the barracks. He asked which one would I like. I had heard of

Minneapolis, so that way my answer. Then he asked where I was from and when I said Cincinnati, he pointed out that

Gross Ile was closer to Cincinnati. I said fine. Two weeks later, I was on my way with my rifle and sea bag,

except this time I went by train at government expense.

Training Base

When I arrived, I found myself at a training base for Royal Canadian Navy Cadets. There were about six Marine

and six Navy pilots serving as primary instructors. The mechanics were a mixture of Navy and Marine personnel,

mostly from the Detroit area. We had two models of trainers, the NP-1, made by Sparten, and the N2S, made by

Stearman. Both were yellow perils with open cockpits. I had been working on these aircraft about three months when

the maintenance officer, Lt. Meirs, came in one day and said to take the spoiler off of the NP-1. It was a

three-quarter-inch triangular piece of balsa wood, covered with cloth. The problem was that every time someone

bumped it, there was damage and it had to be replaced. Another mechanic and I removed the spoiler and covered the

leading edge with cloth and painted it. It looked good and smooth. On April 3 (Good Friday), Meirs was ready to

flight-test the aircraft. I asked to go up with him, and he told me to be ready right after lunch. I checked out a

parachute. The chief who issued it said the chute was too big, but I said that it was all right, that we would

only be gone a few minutes.

Well, we took off and Meirs climbed to 3,000 feet and put it into a spin to the right, recovered and climbed

back to 3,000 feet and put it into a spin to the left. The spin lasted longer than I thought it should have and

Meirs started yelling something, but I couldn’t understand him. Then I saw him climbing out of the aircraft. I

tried to lift myself up, but the force of the spin kept me in the seat. I put my hands on the side of the cockpit

opening, then tumbled out on the inside of the spin. I reached for the rip cord, but couldn’t feel it. I threw my

goggles off and the cord was back under my left side. When I did pull the cord, my hand came flying up to the

right. I could see the D-ring, but couldn’t see the cable that was supposed to be attached. I looked at my hand

when I saw the silk go by and felt a mighty jerk. The chest strap was under my chin and I couldn’t see down. I

didn’t know much about parachutes, but had heard that you could unbuckle the chest strap and hold the risers with

your hands. I did this and low and behold, I was right on top of a 100-foot water tank. I had also heard you could

pull either riser and drift in that direction, so I did this. From the leg of the water tank were three

high-tension power lines, but there was no time except to cross my legs and go between two of them. I hit the

ground and the chute bellowed out over the wires. I unbuckled and stepped out. Meirs was about 50 yards away. The

aircraft landed in the parking lot of a railroad repair station and wrecked seven automobiles. The fellows at the

railroad station saw the whole thing. They said my chute opened at about five hundred feet.

Meirs and I both went to sick bay for a physical check-up and were released. By 4 p.m., I had a hell of a cramp

in the calf of my right leg. Guess the tail section had clipped me in the leg and I didn’t realize it until later.

That evening, the Detroit paper came out with big bold headlines, "U.S.S. Langley Sunk." Just under that, but in

smaller print, the article stated that two Navy flyers stuck to a plane to save the town. It sounded good, but

that wasn’t the way it happened.

Flight Program

Shortly thereafter, I heard that the Marine Corps was taking some enlisted men into the flight program. I went

to the commanding officer, Major Charlie Adams, and asked for flight training. He said that after my experience

bailing out, if I learned to send and receive six words of Morse Code a minute, he would see what he could do. A

sailor named Bill Gray and I rigged up a key button and started practicing. By August 1, 1942, we could send and

receive maybe two words per minute. I went back to Adams and told him I was ready. He sent a request to

headquarters and by the end of August 1942, I had orders to report to pre-flight school at Athens, Georgia. On

Nov. 24, 1942, I arrived and entered the 13th Battalion; Bill Gray was in the 12th Battalion.

I made buck sergeant by the time I reported to Athens. Here, I was back in school with 45 cadets and four Navy

enlisted and one Marine sergeant. Everyone wore the same uniform, so except for liberty, no one could tell the

difference. However, the enlisted could stay out on the weekend and the cadets had to be back by 10 p.m. This got

me in trouble later with one of the cadets. The weekend that we finished pre-flight school, I rented a room in

Athens for a party. We all had too much to drink. I made sure the cadets all got back to Langley Hall by 10 p.m.

However, the cadet who had to bunk above John Urell got sick and vomited all over John’s freshly cleaned and

pressed uniform, which he was to wear at E Base in Dallas the next day. John got all over me for that one. I ran

into him at El Toro in 1950. He was a major and I had reverted to master sergeant. He didn’t let me forget that

incident, as we were both in the same squadron. We left for Dallas March 1, 1943 and I made my first flight on

March 17, 1943. I got every flight I could and had more than 100 hours by the time I left for Pensacola, Florida.

One day I looked over the schedule board and there was an airplane available. I requested it and told that if I

could make it off with the group going out, I could have the flight. Well, I jumped into the N2S, started it and

taxied out, climbing up with the rest of the group. I was in the acrobatic stage so I went to that area and did a

barrel roll. But by the time I got half way around I knew something was wrong. I got the airplane upright by

holding on to the stick and throttle. I had failed to put on my seat belt, and my knees were shaking so badly I

thought I would never get it fastened.

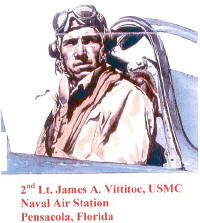

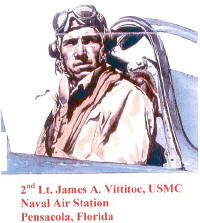

Pensacola

Shortly thereafter, I was on the way to Pensacola as a staff sergeant. When I checked in, I was assigned to

Saufley Field for formation flight in an SNV, then to Cavilier Field for instruments. From there everyone was sent

to a field that would indicate what type of aircraft he would fly in the fleet. I asked for fighters and was sent

to Barron Field, called Bloody Barron. I was assigned to a flight of six; one other enlisted pilot, Bill Brockman,

and four Navy lieutenants, all academy graduates who had come back from the war zone—Lt. Seaman, Lt. Brown, Lt.

Craft and Lt. Bronson. Only Seaman made it through the war. Brockman and I walked a straight and narrow path, but

the lieutenants didn’t take guff from anyone. They kept us in trouble all the time. During that period the

commandant put out a letter to all enlisted pilots saying that if they were interested in a commission, to have

two officers make the recommendation. These four made a recommendation that should have promoted Brockman and me

to colonels, at least. I saw Seaman after the war as a Navy captain in Washington, D.C. One of the instructors

made a statement to us during the first week at Barron that would hold true. He said, "If you guys can get through

the hot-rod stage and make about 500 hours without killing yourselves in some dumb operational accident, you may

have a chance to live a full life." He was right.

Melbourne

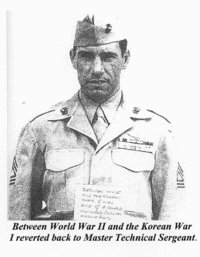

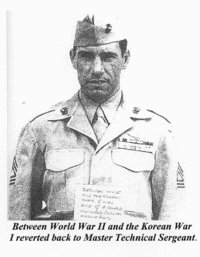

I finished Pensacola and graduated on Sept. 14, 1943 as a master sergeant. Brockman made second lieutenant and

stayed at Pensacola. I have not heard from him since. I got orders to Melbourne, Florida; why, I’ll never know.

Most Marines went to Jacksonville for operational training. I checked in at Melbourne, the only enlisted pilot on

the base. Melbourne had F4Fs and the new F6Fs. The Marines were now flying F4U/Corsair. Any flight they had a

Marine in the group flew F4Fs; the Navy pilots got F6Fs. They didn’t know what to do with me, the only enlisted

pilot, so I stayed in the Marine barracks. By the end of September, I was appointed a second lieutenant. The

Marine Corps said I could stay in the barracks for the two remaining weeks of training if I didn’t wear the second

lieutenant bars on base. I agreed.

The F4F had very narrow landing gear. My first flight was to be a touch-and-go flight in the pattern. Well, on

my first takeoff I felt something that I thought was a blown tire. I told the tower my problem and flew around

Melbourne for an hour. But I had to land sometime, so I told the tower I was coming in. When I touched down, the

plane started veering off to the left. I let it go and it ran off the runway and stayed upright. I had no problem

with the narrow landing gear after that. We had an Ensign Santana who ground looped three before they grounded

him. When I left Melbourne they didn’t know what to do with him. Two years later I ran into him at Floyd Bennett

Field. He had gone into the ferry command from Melbourne and was checked out in almost every airplane in the Navy.

The F4F had a Curtis electric prop. On a bombing run I had a runaway prop. I thought it would fly off before I

could get it under control. I finished operational training the last week of November 1943, one year from start to

finish. The only thing left was to get a check out in the F4U/Corsair at El Toro on the way to the South Pacific.

El Toro

I left Melbourne for Cincinnati around the first of December 1943, a new second lieutenant. When I arrived in

Cincinnati on my way to El Toro, California, all the gang was gone. Mother was still working at the sanitarium; my

brother Lloyd had joined the Marine Corps and was in Guadalcanal with the 1st Marine Division. Hagan, my youngest

brother, was in boot camp at Parris Island. Mom and Pop Lawson were getting old and both were in poor health.

Verna and I saw a few movies. I had a few meals at the Turkelsons. They always set a great table. Charlie was at

Hunter University in New York as a DI for women Marines. The old town was not what it used to be. Verna drove me

to the train station and I was on my way to California and the South Pacific. I remember at the train station the

loud speaker was playing the hit of the time, "Sentimental Journey." How true!

I arrived at El Toro and was assigned to a flight with three other pilots: Ralph Thomas from Idaho, Rob Roy

from Washington state; and Preston Kaymier from Virginia. Our instructor, Capt. Trenchard, who was just back from

the Pacific, said he voted Kaymier most likely to spin in. Kaymier stayed in the Marine Corps after the war and

was killed in an automobile accident in Hawaii in 1970. Trenchard was killed at Mojave three months after we left

El Toro.

The first woman Marine I saw was at El Toro. She was the shuttle bus driver between the BOQ and flight line.

She said she went through boot camp at Hunter College in New York. I asked her if she knew a DI there by the

name of Turkelson. Well, Turk’s ears must have burned. A drunken sailor could not have used more profanity in

describing him. Turk had made her and a girlfriend scrub down a stairway with toothbrushes.

Who should I find at El Toro but Lt. Cargill, now a major and commanding officer of a diver bomber squadron,

and Major Charlie Adams, now a colonel and executive officer of the base.

We flew every day through January and February of 1944. When we weren’t in the air we were living it up in

L.A., mostly at a bar called Mike Lyman’s in Hollywood.

One night in early February we were assigned night-flying duties. The four of us were beginning to have a good

feel for the ole Corsair. The moon was bright and on landing I was leading the section, with Thomas on my wing. We

were to stagger our landings. Rob landed first on the left side of the runway, and Kaymier on the right. I was on

the left and Thomas on the right. I had just touched down, when I noticed Kaymier cutting across the runway in

front of me for the taxi way. I poured the gas to the Corsair and went around, pulled the wheels up and left the

flaps down, made a tight turn and landed right behind Thomas. But as I landed sparks started flying in all

directions. When it stopped, I jumped out and ran. When I looked back, I realized what I had done – landed wheels

up.

The next morning I was in front of the executive officer. For 30 minutes he gave me hell, telling me that

aircraft cost $60,000, and I was restricted to base for 10 days. When not flying I was to stay in the BOQ. Then I

had to go see the commanding officer. He agreed with the executive officer, but added one thing. He said I should

take that Corsair as high as I could get it. I’m not sure he wasn’t trying to get rid of me. I made 43,000 feet

and at that altitude it was a very wobbly aircraft. To keep from pulling the wing off, it took me almost as long

to get down as it did to get up there.

We needed transportation, so we would get a rental car with limited mileage. Gas rationing was on but we could

get gas from a station in Santa Ana. We had a hard time paying for the rental, though, so someone decided to

loosen the speedometer cable under the dash. We drove the rental car all week that way, then put in the proper

amount of gas and hooked up the speedometer just prior to taking it back.

During this time the Army was training pilots in P-38 at the ole Santa Ana Army base. We used to mix it up and

that was encouraged until someone in a P-38 tried to loop a flight of Corsairs and hit and killed the lead Marine

of a flight of four.

Bob Wright, a flight buddy, found an old LaSalle and bought it for $300. We used that until we got orders and

drove it to Miramar, which was an overnight stop prior to getting aboard ship. We tried to sell the car, but there

were no takers. We ended up giving it to some sailor who had just returned from the South Pacific.

Overseas

We boarded the USS Salvo Island and on March 15, 1944, my birthday, sailed on the shakedown cruise to Esprito

Santos in the New Hebrides. This took 30 days because we zigzagged all over the place to stay away from Japanese

boats and subs. We stayed there two days and then were sent to a southern island called Efate to joint he fighter

pilot pool. When the squadrons came south, those pilots who had three tours of combat were sent home; their

replacements and those killed were taken out of the pool. While there, we continued to train.

On one occasion 12 Corsairs were to cover 36 dive bombers. They were to do the navigation as we were doing a

weave well above for their protection. The target was covered by clouds and they were lost. We had no idea where

we were; there was no land in sight. The fighter pool C.O. got concerned as we were well overdue. He had a

radioman start calling, and we picked up the call. He took a radio bearing on us and said we were at 070 degrees

from the base. By this time everyone was on his own. The bombers had fuel, but the Corsairs were getting mighty

low. One Corsair pilot had already jettisoned his canopy, ready to ditch. When we saw land we were between

airfields; one called Havana Harbor and the other, our field, called Qoin Hill. I was almost to the beach

indicating 10 gallons of fuel when the ole Corsair engine quit. I lowered the flaps, left the wheels up, and just

as I was raising the nose to make a water landing, one side of the flaps started coming up. I managed to keep it

level with rudder as I hit the water. As I started settling into the water, the nose hit the coral reef below the

water. All I could think of was that it would flip over, and I would be pinned between the coral and the aircraft.

Luckily, it stayed upright. In fact, I could still use the radio. I called the base and told them where I was –

two miles from the runway with nothing but trees between there and the beach. Two pilots made the trees and were

killed. One landed just short of the strip at Havana Harbor and wrecked the plane, but the pilot was okay. I was

four hours and fifteen minutes on that flight. In 1950, I read in an aviation magazine that at low tide the

Corsair would come up out of the water, which indicated there had been an airfield in the area at one time. In

1990 I returned to Efate with my son Craig and daughter-in-law Suzanne. We found the Corsair. It was in fair

shape, considering it had been in salt water for 46 years.

[KWE Note: "Return to Efate" is found in the

Appendix of Jimmy Vittitoe’s Memoir on the KWE.]

I joined VMF212 and headed for Green Island in the Salmomans, just north of Bougainville. We had a bomber strip

and a fighter strip on Green which was only five miles long and about two miles wide. There were three fighter

squadrons on Green Island: VMF212, 213 and 214. Our main target was Raboul on New Britton, a large island off the

east coast of New Guinea. Raboul was the largest Japanese base in the South Pacific. They still had aircraft;

however, by the time I got there they would not bring them up. They would taxi them down the runaway to try to

draw us down. They had the most concentrated fire power in the Pacific. On the first flight to Raboul, Lt. Wilson

led us through Simpson Harbor. (The flight was made up of Wilson, with me on his wing. The section leader was Lt.

Knudsen and tail-end Charlie was Lt. Al Semb. We remained as a team for my first combat tour.) I have never seen

so much fire power. How we got through without getting hit is beyond me.

New Ireland was about 10 miles east of New Britton, and on the southern tip was a point called Cape St. George.

At this spot were the best Japanese anti-aircraft gunners in the South Pacific. There was nothing there but gun

emplacements. We gave it a wide range. Lt. Prestrige was leading a flight one day and decided to give them one

bomb and a strafing run. They hit him. The shell went down from one end of the Corsair to the other. He got home,

150 miles over water, but the Corsair was junked. Prestrige flew wing on the commanding officer for the next two

weeks. We lost the first pilot a week into our operational tour. Lt. Semberviva was hit in the fuel tank and

losing fuel like mad. Halfway back to Green Island, the fuel was gone and he had to ditch at sea 75 miles from

home. He got out of the aircraft but didn’t use dye marker and was never found. We heard later that he couldn’t

swim. I knew several other pilots who couldn’t swim either. How they got through flight school, I will never know.

By August I had completed my first tour and was going to Sidney for R&R. The squadron of 15 aircraft had lost

six pilots during that tour. Wilson went home; this had been his third tour. We had a ball in Sidney for seven

days, and then it was back to Green Island. During this time the only news from home were letters from Mother and

Verna. Mother kept me up-to-date on Lloyd and Hagan. Lloyd had been hit in the arm with shrapnel from a grenade.

Hagan was on the landing at Palau. We were all three overseas at one time for a short period. Verna kept me posted

on the fellows from College Hill. I’m not sure I ever told her how much I enjoyed her letters.

My second tour was the same operation as the first except that this time I was a section leader and Knudsen was

the division leader. My wing man was Bob Wright. We escorted bombers and made strafing runs before the bombers

came in with their bombs. I still don’t know how I ever got through that tour without a hole in an aircraft. I

have made strafing runs where I could see the tracer bullets come directly at me, then seem to separate and go by

on both sides of the cockpit. Our biggest find on this tour were five fully loaded fuel barges in a cove on New

Ireland. What a fire! We all got the distinguished flying cross for that and 56 other missions, but still no

Japanese aircraft. The only one I saw flying in that area was when we were escorting a C-47 from Green Island to

Emirau off the north end of New Ireland. We saw a zero off the coast and started for it, but the pilot of the C-47

saw it too and yelled, "If you bastards leave me, I’ll have you all court marshaled!" We stayed with the C-47;

Rolo Hielman got it a few days later.

My second tour was up and we had one more flight. It was a dusk patrol over Green Island. We took off fully

loaded. Knudsen was leading. We climbed to 10,000 feet. Things were slow; no action. Knudsen was heading home the

next day and the rest were going to Sydney. He said to follow him in a loop. He didn’t have enough speed for our

altitude and weight. When I was at the top of the loop, I was out of speed. I knew Bob Wright could never make it.

I looked back to see how Bob was doing, and he’d spun out. He stopped the first spin but went right into a

progressive spin the other direction. All I could do was watch and hope he could get the spin stopped and pull out

before he hit the water. I saw him stop the spin and start the pull out. He had vapor streamers the full width of

the wings and cleared the water with less than 200 feet. The next day we were off to Sydney. Bob said he was sure

glad to be with us. We lost four pilots on that tour.

On Nov. 8, 1944, I headed for my second R&R in Sydney. Our transport pilots this time were from the Army Air

Corps, both second lieutenants, flying a DC-3 from Bougainville to Townsville, about a six-hour trip. Everything

was going great until about midway through the flight when these two yokels spotted a huge thunderstorm—and plowed

right through the middle of it. With nothing but fighter pilots (15 to 20) in the back, it was a mistake on their

part. We were thrown all over the place. No one was strapped in. When they broke out on the other side of the

storm, a major and captain were just about to throw them out the door. Needless to say, after that they stayed in

the clear to Townsville and Sydney.

The normal R&R was seven days in Sydney, and each of us had taken the money required for a seven-day tour. The

Australian Hotel had a bar that went through the hotel from one street to the other. The Army Air Corps had their

bar, Army had theirs, but this one was for Marines. Freida Hall was the barmaid. She had every Marine squadron

patch on the back bar wall with names and pictures of all the Marine aces. When our seven days were up and we were

out of money, there was no airplane to take us back. We found out that MacArthur had returned to the Philippines

and the transport aircraft were being used to move personnel there.

Each week, we borrowed 10 pounds (about $35) from the Red Cross. When we got back on Dc. L5, 1944, there was a

letter from the Red Cross asking us to pay up. The day we were back in Corsairs flying to Raboul, we learned Lt.

Zanger had been shot down that morning and had bailed out near the water. We found his chute in the trees but he

never made the beach. We don’t know whether he made it as a prisoner or was killed.

The squadrons were reorganized and headed for the Philippines. This was my last tour and I was now the division

leader. On my wing was Lt. Wilder. He was killed at Cebi City, from ground fire. Section leader Tom Mooney, who

later flew F86s, was an exchange pilot with the Air Force in Korea and after retirement, flew one of the Corsairs

in the movie Ba Ba Black Sheep. He was killed in 1987 flying a sea plane in the Caribbean. Frank Tallman of Tall-Mantz

fame (Orange County Air Museum) was returning from San Francisco to be a pallbearer for Tom when he hit Saddleback

Mountain and was killed. Tail-end Charlie was Brian (Dumbo) Graham who retired as a test pilot from Sikorsky

Aircraft in 1980.

We were also assigned to a new squadron, VMF222. (The pilots were accustomed to being shifted around from

squadron to squadron.) We left Green Island on Dec. 9, 1944 and headed to the Philippines. We arrived at Samar on

the Gulf of Layte, after 15 hours of island hopping—Green to Emirau to Biak to Pelelieu and 600 miles from

Pelelieu to Samar. Should anyone have to ditch, there was one P.B.Y. sea plane somewhere between. Everyone made

it, but the last 200 miles was through one of those South Pacific storms. It rained so hard you couldn’t see 20

feet. Our escort and navigation plane was a B-25. Fifteen Corsairs were tucked in so close the B-25 couldn’t make

a turn without notifying us. We arrived on Jan. 12, 1945. MAGII had arrived two weeks earlier. They had heavy

losses in both aircraft and pilots.

My first mission was two days later. My division and one other escorted two DC-3s to Mindoro with supplies. The

strip was too small to handle the DC-3s and eight Corsairs; we had to circle while the DC-3s were unloaded. We had

belly tanks: 300-plus gallons of extra fuel. The flight took nearly seven hours. When we arrived home we made the

standard fighter break. I lead the second division which made me number five to land. When I reduced power to make

the landing the engine quit. There was no place to go except the strip, so I dived for the strip in between two

landing aircraft. I made it, but with the speed I had, I hit the tail of the Corsair ahead before I locked the

brakes and nosed up. No one was hurt, but both planes were used for spare parts.

Our major job was flight cover for the Navy convoys and after release by other aircraft, we hit any target of

opportunity. This was the fun part of the flight. We all used the water from our canteens to our on our heads to

keep from going to sleep. It was hot and humid. On one of those Layte Gulf patrols I had an engine failure. I dead

sticked the ole F4U into the Tacloban Airfield along the beach where MacArthur waded ashore on his return to the

Philippines. We would cover these convoys as far as 200 miles out. The early-morning flights would take off two

hours before dawn and get over the convoy prior to daybreak and the other would stay until after dark. We lost

several pilots on those missions. There was no weather briefing to speak of and just fly dead reckoning to the

area. With radio silence sometimes a pilot would be missing and none of the others would know it until the sun

came up.

We had three major accidents on the Samar strip. The executive officer was taking off on a pre-dawn flight and

another Corsair was taxing down to take off. The tower had cleared the takeoff but not the taxi aircraft. Both

lived but were badly burned. The second was a B-24. We shared the strip with a B-24 squadron. They were bombing

Okinawa from Samar. The strip was narrow so the lead B-24 on a takeoff drifted near our parking revetment area,

and a Corsair turning up cut a portion of his wing off. The B-24 crashed just off the end of the runway, and all

aboard were killed. The third almost wiped out the squadron. I was the duty officer this particular day and was to

record each aircraft as it took off. Pilots had been going to the revetment area and if their assigned aircraft

was down for any reason they would just take another. The maintenance officer and I were standing amidst our

tents, operations, parachutes and maintenance as the first division took off and I recorded the numbers. The first

aircraft of the second division took off and as the second aircraft was about to lift off, he hit a hole in the

runway and blew a tire. The aircraft swerved toward us. We could see that Corsair coming directly at us, and we

both ran like hell. The wheels of the Corsair caught the first tent and took out the other two. Just as the

maintenance officer and I stopped running and turned to see the damage, the aircraft exploded in our revetment

area. The Corsair ended up on its back, and Lt. Orth was knocked out. The mechanics in the revetment area rushed

in to get him out. Fourteen men were killed and many others hurt. Several other aircraft were damaged.

In April 1945 my third tour was over and the squadrons were heading for the Marianas, getting closer to Japan.

During that year I had flown 111 missions, seen some outstanding pilots lose their lives and never saw one that

didn’t face the dangers head on. Most were very young and eager. The older ones were cool, but they too were

eager. Some were high school graduates, some had masters degrees—yet in the aircraft you couldn’t tell one from

the other. It is said that the military is the great leveler, and it was proven overseas.

Back in the States

On the way home, I stopped in Hawaii for four days awaiting transportation. Verna had told me Bob Keifel was

stationed there, so I looked him up. We tried to drink the island dry, fought the war over again and caught up on

the ole gang. I got out of Hawaii on the Pan Am clipper which had eight bunks and ten plush seats. I was still a

second lieutenant so I didn’t have the rank to get a bunk, but who cares. I had made it through a very tough year,

and 14 hours later I would be back in the good ole U.S. of A. in San Francisco.

We arrived there just as the first United Nations meeting was being organized. We all headed for Harris and

Frank clothing store to get new uniforms, a few ribbons, and then on to liberty in ‘Frisco. We had a ball for a

couple of days until my wallet was stolen. I had to borrow enough money to wire Mother to send me what little I

had saved during the year. I never cared much for San Francisco after that. We then went to Miramar for

assignment. I was asked what I wanted: East Coast, West Coast, or ferry duty. I said ferry duty. This time it was

by train with a room. Rob Roy and Ralph Thomas had picked the same duty, and there were several others I had known

from other squadrons on the same train.

From Floyd Bennett Field in New York we went to Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, to check out in the various

aircraft we would be flying. As fighter pilots there wasn’t much choice, F4Us and F6Fs. The F6F was much slower so

the Marines tried to stay with the F4Us, but the Navy saw that we took our share of F6Fs. We would leave Floyd

Bennett Field for San Diego with new aircraft for the fleet. The major stops were Spartanburg, South Carolina;

Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; Shreveport, Louisiana; Ft. Worth, Texas; El Paso, Texas; and then San

Diego. Per diem was $7 per day. Hotel was $4-$5, and food and beverages took care of the other $2-$3. The routine

was to deliver the airplane to North Island in San Diego and catch a commercial airline back to New York. We had

top priority, so at times the aircraft (DC-3s, either American or United) were loaded with ferry pilots. Take a

load of fighter pilots, put their parachutes in the cargo hold, and fly through thunderstorms from San Diego to

New York for 10-14 hours, and you have real panic on your hands. When we got back to New York, most paid $5 a

night (special rate) to stay at the Pennsylvania Hotel just to get off the base.

Janet

In early July 1945 I was sitting in a bar on 42nd Street with several friends. For some reason I left the

group, and as I stepped out on the street two good-looking girls walked by. I invited both back inside for a

drink. It turned out they were sisters from Altoona, Pennsylvania. One was going to nursing school at Flower 5th

Avenue Hotel. The other was visiting from Altoona. Neither girl drank except for an occasional glass of wine, and

the evening was young when Janet said she had to get back to the hospital by 10 p.m. I took her back by cab, got

her phone number and told her I would call when I got back in town. I made two or three trips before I called.

When I did I wasn’t sure I would recognize her or that she would recognize me. I figured my uniform would help

some, but there were uniforms all over New York in those days. Anyway, we agreed to meet by the statue at

Rockefeller Plaza. We went to dinner and saw the show, "Up in Central Park." Janet had to be back at the hospital

by 10 p.m.

This went on for several months every time I got back in to town. She ate with such gusto that I was beginning

to think the hospital didn’t feed the poor girl. We had our favorite place, Kelly’s Steak House. (Forty-eight

years later, she still has an appetite!) I kept ferrying aircraft and feeding Janet. It was late in August or

early September when I got back from a trip and Janet had a couple days off. New York was hot and humid so we

decided to take a train up the Hudson, not knowing where we would end up, which was somewhere in the Catskill

Mountains. We swam and went horseback riding for two days, and then it was back to New York and the routine.

Post-World War II

I had just landed at North Island when I heard the Japanese had surrendered. The Navy put out the word that no

alcohol could be served in San Diego, not even a beer. I got the first airline I could back to New York where the

parties were still going on. Sometime during this period the Floyd Bennett ready room was full of pilots set to

ferry aircraft all over the country. They were just waiting for the weather to clear when over the speaker system

came an announcement that a B-25 had hit the Empire State Building at the 82nd floor. It was a weekend, so the

loss was not so bad as it could have been.

By the end of October all Marine pilots were transferred to N.A.S. San Pedro, near Long Beach. Our job was to

move the aircraft that we had flooded California with to various stations throughout the country.

The BOQ was full so we had to find our own quarters in Long Beach. Rob Roy, Ralph Thomas, Charlie Chop and I

moved into the Terry Apartment on Ocean Boulevard in Long Beach. This was the first time I had ever seen a Murphy

Bed, but I didn’t have to worry about using it much because we were always on the road. We were to pay rent

weekly. The lady who ran the apartment house could get more by renting weekly. We finally solved that by each

leaving her a check for our weekly charge. I tried to get any aircraft going to the East Coast, then catching a

Navy transport to New York to see Janet. If there was nothing ferrying out of New York, I would go commercial.

Late one night when I returned tired and dirty to the Terry Apartment, I heard a noise before I opened the door.

When I stepped in there were strangers all over the place. One girl asked, "Who in the hell do you think you are

breaking in on our party?" The place was a mess. Charlie Chop had started a party two or three days earlier and

had taken off on a ferry flight. I borrowed a key to one of the other pilot’s apartments that night. I cleaned

house the next day.

Rob Roy was from Yakima, Washington. Rob had picked up a Corsair in Whidby Island and had stopped in Yakima to

see his folks. He was weathered in for 29 days, and when he got back he put in for a $2 cab fare each day from his

folks’ place to the airport. The disbursing officer almost court-marshaled him for trying to charge the government

$2 a day. He definitely did not get his cab fare. Rob stayed in the Marine Corps, when to test pilot school, and

was killed on an instrument flight in a Beech-18 in 1948 when the aircraft hit a mountain 75 mil4es west of

Quantico, Virginia.

Ralph Thomas left the Marine Corps and went back to Sun Valley, Idaho and later became the manager of the

Challenger Inn in Sun Valley. He is now retired.

Charlie Chop was called back during the Korean War and became one of the early helicopter pilots. He worked

with me at Hughes in 1964 in Culver City. Later he worked with the FAA as an examiner. I haven’t heard from him

for several years.

In early 1946 people were getting out of the service in droves. In mid-March I decided to give civilian life a

try. I was in Alameda, California, had just delivered an F6F and was told to taken an FM-2 to Olathe, Kansas – the

junkyard for older aircraft no longer needed. I told the operations officer that I was not checked out in the

FM-2. He said I had flown the F4F, which I had at Melbourne, and they were basically the same. I went out to look

at the aircraft. It had seen better days. The aircraft had no log books, but that excuse didn’t work either. So I

was on my way. When I got to Tucson, I discovered a friend was taking a TBM to the same place. I had never flown

the TBM and he had never flown the FM-2, so we agreed to trade aircraft from Tucson to El Paso. We gave each other

a cockpit checkout and headed for El Paso.

Well, this old TBM had an automatic pilot. I called my friend on the radio and asked him how it worked. He

instructed me to line this and that up and when I had that taken care of, push a button. Well, when I pushed that

button, the darn thing almost flipped on its back. I unplugged it and went on into El Paso. When I got to Olathe

there was no transportation back to California. The operations officer said they had a DC-3 going to Wichita,

where there were 12 TD2Cs waiting—six to the West Coast and six to Jacksonville. I had no idea what a TD2C was,

but I found a typewriter and put it on my ferry card and left on the DC-3 for Wichita.

When I saw the thing I knew I had made a mistake this time. It was a small single seater with tricycle landing

gear, which I had never used before. I cornered one of the other pilots and asked a few questions and was told the

engines were made out of reclaimed metal, good for 60 hours, because the Navy was going to use them as target

drones. It was modeled after a pre-war civilian aircraft called the Culver Cadet. I must say it was a "going

little ginney." I brought it back to San Pedro as my last ferry.

When I arrived back at NAS Terminal Island my orders for separation had arrived. I was to report to the Naval

Ammunition Depot at Craine, Indiana for discharge. In order to save money on transportation I hitched a ride on a

PBY going east. The weather was bad through Banning Pass so the pilot, a lieutenant commander, decided to go to

San Diego and then east through Yuma. The PBY was an amphibian that could land on water or land. Shortly after

takeoff I was at the radioman’s station tuning in some good ‘40s music when both engines quit. The pilot headed

for the water just off Huntington Beach and hit it so hard that it split the hull and the ole PBY started taking

on water. He got the engines started and instead of lowering the landing gear out in deeper water, he plowed the

bow into the beach. Everyone got out and before I left the scene the waves were breaking over the top of ole PBY.

I went back to Terminal Island and got another flight east.

When I arrived at Craine, Indiana, I was a first lieutenant. Being a temporary officer, I was put back to my

permanent rank of master sergeant, then appointed a second lieutenant in the reserves, and finally discharged from

active duty as a second lieutenant. Back in Cincinnati, things were not the same. Everyone had to get on with his

life. I was bored. I took a civilian flight instructor’s course on the GI Bill, but flying those light aircraft

was just not cutting it. I was used to pushing the throttle forward and getting results. Push the throttle forward

on an Aronica and not much happens.

Lloyd got home and started looking for a job. Hagan stayed in the Corps and went to China. I finished the

instructor’s course, bought a 1941 Packard sedan, took Dad out of the hospital and drove him down through Kentucky

for a couple of weeks. I drove up to Altoona where Janet was visiting her parents. The only time I ever paid for

flying, I rented a Cub for $6 and took Janet for an airplane ride around Altoona.

By the time I got back to Cincinnati I decided I would try getting back in the Corps on flying status. I

checked with recruit depot, and they wired the commandant for an answer. The reply stated that if I signed up

within 90 days of my discharge, I could come back as a master sergeant. If I signed up after 90 days, I could

return as a technical sergeant. When the answer came back I had been out 88 days. I signed up and the only place I

could make in two days was Quantico, Virginia. I checked in just under the wire at AES-12, NAS Quantico. The C.O.

of AES-12 was Col. John L. Smith, one of the top aces of the Marine Corps and a Medal of Honor winner. When I

checked in at AES-12 I had on my officer’s uniform but no stripes as master sergeant and no bars as a lieutenant.

Smith didn’t know what to make of me. Years later I stopped at headquarters in D.C. and looked up my fitness

reports. There was always this question on those reports: "Do you recommend this man for promotion?" Well, one of

Smith’s first responses was no – because I had refused a permanent commission. I don’t know where he got that

idea. Several reports later he responded to the same question by saying, "Yes, he has more on the ball than most

of the officers in my outfit."

I had been there a month or so when Smith sent four of us (three officers and me as a master sergeant) to San

Diego to pick up four Corsairs freshly out of overhaul. When we got back it happened that I was the only one to

fill out the log books properly. From then on he sent me on most of the ferry trips. AES-12 maintained the

aircraft for school pilots and used them also as a demonstration squadron for Congress, demonstrating new rockets

and bombs. On one occasion Smith was leading two others and me. We were carrying a new rocket called the Tiny Tim.

When we got to the range the weather was bad and we couldn’t drop the rockets. We couldn’t land back of the

airstrip either, so what to do. We flew down the middle of the Potomac and dropped them unarmed. As far as I know

four Tiny Tim rockets are still on the bottom of the Potomac somewhere between Quantico, Virginia and Maryland.

Marriage

My ole Packard came in handy too. Janet was still in school in New York, so some weekends when I had enough

money for fuel and food I would drive to New York to see her. I found a way to supplement my meager wages. John

Gibba, another master sergeant, had to hitch a ride to D.C. each night because he was going to watchmaker’s

school. He would fill the old Packard with four or five Marines for $1 each and stop at an all-night restaurant,

then on his way back, do the same, so by the weekend I would have a few bucks. This went on for almost a year

until Janet and I decided to get married. She left school in August 1947, and then I only had to drive to Altoona

to see her. Sometimes I would take a test hop and fly to Altoona and buzz her house. I was the designated test

pilot for the squadron, so I would file for a local test flight and if I was gone a little longer than normal, no

one knew the difference.

Janet and I were married on November 22, 1947. I had to sell the Packard to have money to set up housekeeping.

We rented a trailer in Quantico. I remember the first meal she prepared. She was going to economize and had bought

some salted fish and forgot to de-salt it or whatever you do with salted fish. We had to throw it out and get

hamburgers. We moved from the trailer to an apartment over a grocery store. I had put in for NCO quarters on the

base and got base quarters just before the roaches ran us out of the apartment.

We didn’t have much money in those days. We did a lot of things that didn’t cost much, like fishing and

hunting. I think one of the most upsetting things for Janet was when I spent $45 for a fishing rod and reel. I

heard about that for years. All in all Quantico was the most enjoyable tour I had in the Marine Corps.

Memorable Flights

Five flights during this tour stand out. The first was another ferry flight to pick up four Corsairs freshly

out of overhaul at San Diego. The flight consisted of Captain O’Neal, a low-time Corsair pilot; Lt. Dan Stith,

technical sergeant; Woody Williams; and me. When we got to Dallas, Stith said he would lead the flight on the next

leg, and we were going by way of St. Louis. I had no maps for the St. Louis area, so I went into operations and

checked out a set of maps. The weather was bad but we managed to climb to about 10,000 feet and headed for St.

Louis. When we got near, we couldn’t raise St. Louis on the radio. We had no idea what the bottom of the cloud

cover was. It turned out that Stith had a set of maps for the area and we were going this way because St. Louis

was his hometown. He was not on a leg of the radio range when he said we would go down. I started down with him

but soon realized I was in a skid. I broke off and went back on top, picked up the radio range and started down. I

decided that I would go as low as 1700 feet as the terrain was 1400 feet, and if I hadn’t broken out by 1700 feet

I would climb back on top and call for help. As it turned out I broke out of the clouds right at 1700 feet and

went on in and landed. It was another 20 minutes before the other three arrived. The lieutenant never said

anything about it. However, Woody said he wished he had broken off with me, as they almost hit the hills just

outside of St. Louis.

The second was a ferry flight from Pensacola. I went to Pensacola to pick up a newly overhauled SNJ. I left

Spartanburg, South Carolina, for Quantico, Virginia, on a Saturday morning. The weather report was marginal, but I

needed to get back. By the time I reached Richmond there was a full-blown snowstorm. After going around a few

flurries, I was overdue at Quantico and the duty officer had called Smith. After flying around, getting nowhere,

and burning fuel, I picked up the railroad tracks from Richmond that went right along side of Quantico. At 500

feet or less, I went home. When I got to Quantico, the field was covered with ice and snow and it was still